Yesterday, I wrote at length about the many disastrous expensive attempts scientists and engineers made in their quest to collect material from the mantle. So far, they’ve all ended far short of their target. Drilling through crust material (granite on the continents; basalt under the oceans) to the mantle is very, very difficult. Perhaps impossible.

This makes the world’s deepest borehole even more astonishing. It was a gallant effort, but the Russians who were drilling the well reached only one-third the way to the mantle. Drilling extended over 24 years, from 1970 to 1994. That was a long time ago, yet the Soviet-era engineers reached a depth of 12,262 metres (40,230 feet). That remains a world record. No one, anywhere, has placed a drill bit deeper.

I don’t want to dwell on the fact that under the Communist system, drilling a superdeep well worked better 40 years ago than any efforts conducted by capitalist countries today. But after reading yesterday’s blog entry about the utter lack of fortitude among the funders of pure science in the enlightened world, you may agree that it’s not that surprising. Big talk of billion dollar projects manifests relatively few bucks in grants. This makes life hell for scientists and engineers who begin to drill into tough basalt, then have budgets killed.

Machines break, gale winds rock exploration ships, drilling gets behind schedule and over budget. I’d hate to be the science director answering the phone when someone like Ted Cruz calls to ask why we haven’t yet drilled deep enough to hear screams from Hell. What would you tell your senator/rep/MP? “If you give us more money, we’ll reach the mantle, for sure. Meanwhile, can I send you a nice piece of gray basalt we recovered last month?”

If an autocratic government seeking international prestige (like the USSR) is determined to commit to a project that will last decades, then funding can continue through inevitable setbacks. None of this is intended to detract from the Soviet scientists and engineers who actually did the work. They were brilliant. For most of them, the goal was discovery, though nationalistic pride was also a likely factor.

The Kola Peninsula Superdeep Borehole will be remembered for its remarkable depth and the tenacity of its drillers, but there was a breadth of knowledge gained as well. First, we’ll look at the engineering. Before the Kola well, deep wells rarely passed 1,000 metres. The Russian scheme expected its initial phase to reach 15,000 metres.

Early Deep Wells

The first deep wells were drilled 4,000 years ago by Chinese engineers. They built rigs of bamboo and dropped heavy chisels that punched a hole in the ground. Some of these wells took generations to drill, and the deepest reached nearly 1,000 metres.

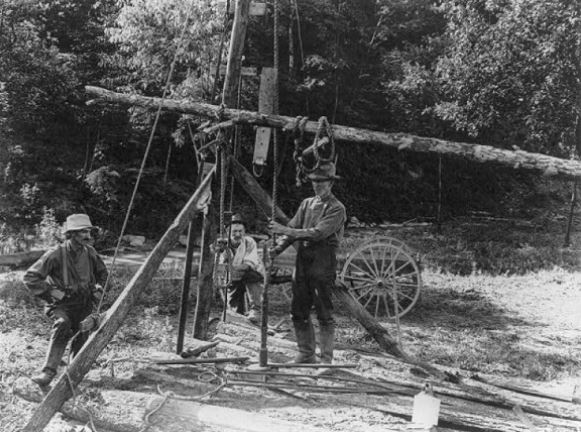

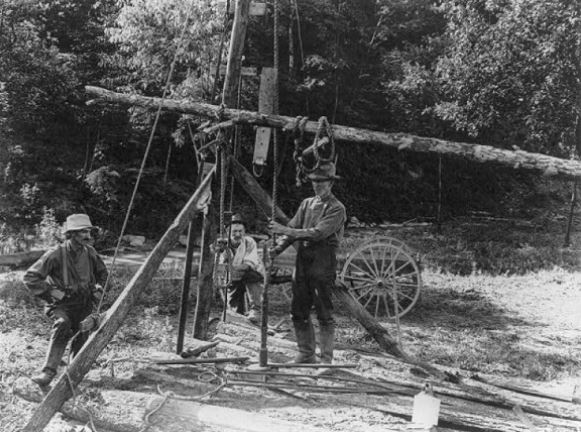

Spring pole drilling rig, 1806

In Europe, wells were hand dug and water was the usual target. Around 1806 in the USA, the Ruffner Brothers invented the pole spring rig to hammer through bedrock to reach salt brine, a scarce commodity at the time. Theirs was the first American well known to be drilled instead of dug. The spring pole was a 10-metre tree trunk that was lifted a couple of metres above the ground at one end and anchored in the ground at the other. A fulcrum was fixed in place to keep the elevated end up and allow it to “spring” back after it was pressed down and released. This allowed a combination of gravity and springing action to do most of the work. The driller would work up a rhythm, bouncing the free end of the pole up and down while an attached rod with a chisel chipped a hole into the rock below. Pole spring wells often drilled hundreds of feet, usually searching for fresh water. It was an adaptation of the pole spring that was used in Titusville in 1859 to drill the first American oil well. Even today, rigs based on the idea are used around the world.

Spring Pole Drill, 1924, (US Dept Interior photo)

The next major innovation in drilling deep wells required attaching a drill bit to a long series of iron pipes. Drillers spun the entire contraption at a high speed. This meant that all the pipes from top to bottom in the borehole turned rapidly. Their considerable weight pushed the drill bit into the rock below. Water and drilling mud were forced down the pipe to wash out the chips chewed out of the bedrock. In 1938, a California oil well almost 5,000 metres deep was completed. Enormous engines spun 200 tonnes of alloy steel pipe, forcing the drill bit deeper into the Earth. That was still the state of the art when the Kola well was being designed by the Soviets in the 1960s.

Kola’s Deep Drilling Technology

A key objective of the Kola well was to develop technology to drill extremely deep oil wells. The scientists on the project created a new way of drilling that revolutionized the way the task is done.

The Russian drillers realized that they could never gain enough torque to quickly spin 15,000 metres of pipe, which could weigh 600 tonnes. They used aluminum alloy pipes to reduce the weight of the pipe string, but they figured that it still wouldn’t work. In addition, the tubing would need to be pulled out of the hole every few days to replace dull drill bits with sharp ones. Lifting the pipe would take an enormous rig so in 1970 the engineers built a derrick 27 storeys tall. It was sturdy enough to hold half a million kilos of dead weight.

But with a depth of over 10,000 metres, the planners knew that no engine would be able to rotate the entire drill stem fast enough to cut into granite 15,000 metres below the surface. Further, it was doubtful that the pipes and joints would stand the strain. So they invented the first rotary bit. High pressure drilling mud was forced down the inside of the pipe. When it reached the drill bit at the bottom of the well, the mud spun a turbine that turned the bit at an optimal 80 revolutions per minute. This simple but elegant design revolutionized the drilling business. There were more discoveries coming from the well. Soviet geologists at the rig made an important find that changed the way we understand the crust.

But with a depth of over 10,000 metres, the planners knew that no engine would be able to rotate the entire drill stem fast enough to cut into granite 15,000 metres below the surface. Further, it was doubtful that the pipes and joints would stand the strain. So they invented the first rotary bit. High pressure drilling mud was forced down the inside of the pipe. When it reached the drill bit at the bottom of the well, the mud spun a turbine that turned the bit at an optimal 80 revolutions per minute. This simple but elegant design revolutionized the drilling business. There were more discoveries coming from the well. Soviet geologists at the rig made an important find that changed the way we understand the crust.

A New View of the Crust

A better understanding of the deep crust was expected to help future oil and gas exploration. The Kola well found resource minerals in the granite at great depths. Kola was spudded on the continental shield 250 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle. This is in an area rich in copper and nickel. The Soviets hoped they would learn something from their well that would help predict other mineral-rich terrain. They also wanted to discover the physical nature of the deep crust itself.

Among the unexpected finds were fossils at 6,700 metres, gas release at all depths (helium, hydrogen, nitrogen, and most unexpectedly, carbon dioxide), and lots of hot mineralized water kilometres below the surface. The water was not predicted at the time and gave a new view of the makeup of our crust. They also encountered much higher temperatures than expected, making drilling more challenging and contributing to the decision to terminate the project.

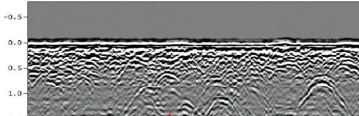

The scientists discovered that the basic rock material deepest in the well was different quite from what most geologists had predicted. In 1926, the influential British geophysicist Harold Jeffreys had postulated that the Earth’s crust consisted of three layers. In Jeffreys’ model, sedimentary rocks covered granite which lay atop basalt. Jeffreys believed basalt could be found everywhere on Earth, just above the mantle, if we dug deeply enough. Supporting evidence for this idea was a velocity increase in seismic waves at about 9,000 metres. This, claimed Harold Jeffreys, was where granite gave way to basalt.

Jeffreys didn’t expect to be proved wrong in his lifetime but he was. Jeffreys’ theory was disproved when the Soviet drill bit found granite – not basalt – at the velocity anomaly. The granite is metamorphosed, making it denser, thus carrying seismic waves more quickly.

Harold Jeffreys, by the way, fiercely refused to accept plate tectonics. He was one of the leading senior scientists who tried to kill the nascent theory. Jeffreys never publicly recanted. Even as a 95-year-old emeritus in the late 1980s, he continued to believe that it was physically impossible for the planet’s crust to drift. But evidence from the Kola borehole supported continental mobility by showing continents to be entirely granite and quite different from basaltic oceanic crust.

Culture, Religion, and the Superdeep Borehole

The Kola Superdeep Borehole was planned in the 1960s and drilled during the ’70s and ’80s. In 1989, the world’s deepest artificial point was achieved, 12,262 metres below the surface. Scientists were considering tactics to fight hotter than expected temperatures. They were preparing to switch to titanium alloy pipes to withstand the ascending heat when their project was shut down.

The rig was idle for a number of years while tests were conducted. By 1992, the Soviet Union was collapsing and the ruling autocracy was momentarily powerless. Funding was cut. Various seismic and petrophysics tests continued, but in 2006 the project was shut down completely. The world’s most important well was sealed. By 2008, even the nightwatchman had left. Today the place is abandoned and decaying.

The Kola well continues to influence our understanding of the deep crust. In a similar way, a deep borehole into the mantle might contribute startling changes to our perception and understanding of the Earth’s interior.

Meanwhile, Kola has inadvertently encouraged some odd religious misconceptions about what lies below us. There are still millions of people in the world who believe that there is a real, solid, literal Hell inside the Earth. Some of these people were elated when they learned – from a fundamentalist group – that the well had to be sealed because the Russians had reached Hell.

They claim that the well hit a hollow cavity and extremely hot temperatures. Scientists lowered a microphone down the borehole and heard the agonized screams of millions of burning souls. Many of the scientists immediately repented and joined the fundamentalist movement. Others fled the site and went insane, as would be expected of scientists who refuse to repent even after hearing the screams of damned souls.

There are plenty of people who are convinced that Satan, not Gorbachev, was the reason the drilling stopped. The story was allegedly first printed in 1990 by the Finnish newspaper Ammennusastia, which was published by a group of Pentecostal Christians from Leväsjoki, Finland. (They sort of put their town on the map, didn’t they?)

A story this remarkable doesn’t stay in a Finnish village. An American Christian outfit called Trinity Broadcasting Network spread it like hot manure all over their network, purportedly claiming it to be proof of the literal existence of Hell. After their original airing, Trinity Broadcasting followed up with more material supplied by a hoaxer. It was a thinly veiled hoax, complete with information Trinity could have easily used to dispel the trick. They didn’t fact check the material. Their trusted reporting and practiced style convinced people that the Russians had indeed opened a door to Hell. Unsurprisingly, according to Trinity Broadcasting, about 2,000 people were led to salvation when they heard the network’s radio and TV broadcasts about the screams from Hell.

.