Over the past few days, I’ve written about Alfred Wegener’s continental drift theory, which is celebrating its 100th year as a spunky idea that explains a lot of our geology. From mountains to earthquakes and deep sea rifts to island arc volcanoes, it’s all tied together in plate tectonics, which began just over a hundred years ago as continental drift.

If you’ve been following my past week’s posts, you saw Alfred Wegener enter our story as a meteorologist, you saw how fossils and climate inspired his theory, then looked at the publication of Wegener’s papers and book between 1912 and 1915, and yesterday, you read about the ugly rejection of his drift theory. Now I’d like to give you a bit about Wegener’s death in Greenland and its immediate impact.

Wegener was on his fourth scientific expedition to the Arctic and he was director of the Danish-Greenland polar research camp. He was much better known around the world for his northern exploration than for his relatively obscure ideas about drifting continents. In fact, the New York Times covered his departure at the start of Wegener’s last trip and charitably did not mention his drift theory at all in their lengthy science article.

Wegener’s fourth mission to Greenland included testing a new seismic method to measure the thickness of the icecap that covered the island. He believed it was much thicker than the assumed 3,600 feet previously measured. Sending sound waves into the ice and timing their returning echoes with seismic equipment would give him a better estimate of the icecap’s thickness. The expedition also involved preparations to establish a permanent station that would gather continuous meteorological data. But food shortages, extremely cold weather, and unpredictable blizzards put outlying camps at risk.

Alfred Wegener and his colleague Rasmus Villumsen were last seen on Wegener’s 50th birthday, November 1, 1930. The day following his birthday, Wegener and Villumsen set off to deliver supplies to a small outlying camp which had been cut off by foul weather. The two were overtaken by a blizzard. Wegener’s body was not found until the following spring, on May 12, 1931. He was lying upon a reindeer hide, placed there by Villumsen, who was never found. When news of his death reached the world, it was front-page news. The New York Times headline read: “Wegener Gave Up His Life to Save Greenland Aides; Left So Food Would Last”.

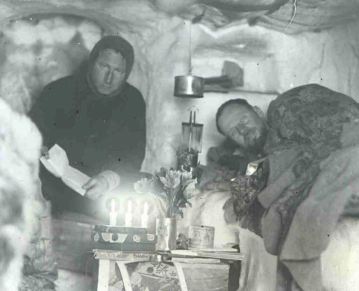

Upon Wegener’s death, leadership of the Greenland expedition passed to his friend Fritz Loewe. Loewe had trained as a lawyer in Berlin, but developed a passion for science and exploration, earning a PhD in physics. He became a meteorologist and understudy to Alfred Wegener. Before the expedition, Loewe had earned the Iron Cross as a young soldier in the German army and had already spent time in the arctic.

During the fatal 1930 expedition, Loewe’s feet froze and a colleague at their Greenland camp clipped off nine of Loewe’s toes with tin-snips and a pocket knife to avoid gangrene. Returning to Germany, Loewe, a Jew, was soon dismissed from his post with the Meteorological Service. He left with his wife and two young daughters for England. He finally found permanent work, in 1937, as a lecturer in Melbourne, Australia, where Loewe co-discovered the southern jet stream. Few students knew the remarkable background of their professor with the awkward gait who clomped the university corridors for 25 years.

Following Wegener, only a handful of geologists were willing to inherit the orphaned continental drift theory. Arthur Holmes, Alexander du Toit, and Reginald Daly spring to mind. They all believed the data and accepted the theory, but they each had busy jobs as geologists – proving drift theory was an interest, but neither an occupation nor obsession. Drift theory did not take a complete hiatus, but the years between 1930 and 1955 saw very few converts to the cause.

Arthur Holmes was born on the moors in north England and educated in London At age 20, he discovered a way to measure the age of the Earth using radioactive decay. He was the first to know that the planet is over a billion years old. Then he figured out mantle convection and claimed that this was the power source that Wegener needed to make the continents drift. The final chapter of his 1944 book, Principles of Geology, is about the mobility of the Earth’s crust. It has the first drawing of the mantle convecting and includes this line: “Currents flowing horizontally beneath the crust would inevitably carry the continents along with them.”

Alexander du Toit was a South African geologist who quickly accepted Wegener’s theory. Some consider Du Toit the greatest field geologist who ever lived. From 1903 to 1910, he travelled the whole of southern Africa on foot, ox cart, and bicycle with a mapping table slung over his shoulders. In 1923, he was awarded a Carnegie Institute grant to travel to South America to test his thesis that rock formations that ended on the edge of Africa picked up precisely the same in Brazil. They do, convincing him that continents had once been joined and have drifted apart. Alexander du Toit wrote Our Wandering Continents in 1937 and dedicated the book to Wegener’s memory.

Alexander du Toit was a South African geologist who quickly accepted Wegener’s theory. Some consider Du Toit the greatest field geologist who ever lived. From 1903 to 1910, he travelled the whole of southern Africa on foot, ox cart, and bicycle with a mapping table slung over his shoulders. In 1923, he was awarded a Carnegie Institute grant to travel to South America to test his thesis that rock formations that ended on the edge of Africa picked up precisely the same in Brazil. They do, convincing him that continents had once been joined and have drifted apart. Alexander du Toit wrote Our Wandering Continents in 1937 and dedicated the book to Wegener’s memory.

Reginald Daly, a Canadian who headed Harvard’s geology department, was a renowned field geologist who visited dozens of countries and every American state (except South Dakota) at least once. His expertise was basalt (“no rock type is more important to the Earth”) and he recognized ocean crust was heavy basalt while continents were mostly lighter granite. Quite early, Daly agreed with continental drift and supported the idea with data he personally gathered around the world. He mischievously put the words E pur si muove! (“And yet, it moves!”) on the cover of his 1926 book, Our Mobile Earth.

Reginald Daly, a Canadian who headed Harvard’s geology department, was a renowned field geologist who visited dozens of countries and every American state (except South Dakota) at least once. His expertise was basalt (“no rock type is more important to the Earth”) and he recognized ocean crust was heavy basalt while continents were mostly lighter granite. Quite early, Daly agreed with continental drift and supported the idea with data he personally gathered around the world. He mischievously put the words E pur si muove! (“And yet, it moves!”) on the cover of his 1926 book, Our Mobile Earth.

I’ll write more, in a few weeks, about Holmes, du Toit, and Daly. They each deserve to have their stories told. They kept the idea of mobile continents alive when almost no one believed them. Besides Holmes, du Toit, and Daly, there were only a few other geologists during the 1930s and 40s who supported crustal mobility theories. Overwhelmingly, established geologists were convinced that the Earth’s continents were immobile. It would take another thirty years before geologists accepted continental drift – modified as plate tectonics. Only then would the names of Alfred Wegener and the others inspire courage of convictions, rather than serve as a stark warning against breaking with scholarly tradition and dogma.

Science, they say, progresses one funeral at a time. This is especially true about the gradual acceptance of plate tectonics. But there is an unspoken (and unknowable) corollary. Science is sometimes stalled by a single death. We will never know how continental drift would have evolved had Wegener not died in Greenland. Had he lived to 1967, the year that nearly all geologists accepted plate tectonics, he would have been 87 years old. He could have lived to see the transition and perhaps even have sped its arrival. We will never know.

I was a student majoring in geography in 1970 and had taken all of the geology course offered. Two fairly young men came to the university to present a talk about this thing called Plate Tectonics. I remember well our Dept Chairman going around to everyone that it was a useful intellectual exercise but “really, continents sliding around the earth?”. As I can recall their names, I wonder to this day who those two guys were, out spreading the new gospel?

Dave Proper

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting comment – by 1970, plate tectonics was largely accepted, but certainly there were still a lot of doubters. It really wasn’t until the mid-1980s when lasers measured actual drift and then, more recently, when GPS became accurate enough to measure cm-scale displacement that the evidence was overwhelming. As a child in the mid-60s, I remember, reading aloud a local newspaper account of drift science and my father laughed aloud at the nonsense. Fascinating that we lived through the greatest geology revolution ever!

LikeLike

As a Glaswegian, I must draw your attention to this remarkable paper by Holmes, 1931 which shows sub-continental circulation, discusses heat budgets, and illustrates continental rifting and subduction; I don’t know why he chose such an obscure location for a piece of work worthy of a Nobel prize and anticipating the 1944 reference that you give: http://www.mantleplumes.org/WebDocuments/Holmes1931.pdf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great link. Holmes was brilliant. He knew it would be hard to get the paper published – nice that the Geological Society of Glasgow printed it.

LikeLike

No fan of the Neal Adams’ Expanding Earth videos, then?

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I don’t think Neal Adams’ expansion theory is right. He’s a great a comic illustrator and some parts of expansion theory may have some valid points, but Adams’s theory is as real as Batman’s cave. I’ve written a bit about this in a new blog entry – here.

LikeLike

Thank You for such a great storytelling!

In biology hovewer, idea was more than alive between 30th and mid 50th, though it proponets, like famous swedish entomologist Renie Malaise were rediculed. But i gues it really was the paper of Willi Hennig (another great, Berlin-bounded german), “Hennig, W. 1960. Die Dipteren-fauna von neuseeland als systematisches und tier- geographisches Problem. Beiträge zur entomologie 10: 221–329. ” which nailed it for biologists…sort of, as Hennig also was called “that german”, especially in USA for quite some time. But then, in 1966 Lars Brundin’s “Real nature of transantarctic relationships” has arrived, and most of young biologists becomes really convinced.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Victor. I do not want to suggest that Wegener worked alone! Your comments are appreciated. Regards, Ron

LikeLike

Pingback: Continental drift – Gondwana – Alfred Wegener (Germany) – ONAFHANKLIK

Even in the year of 1986, when i shared the reality of drifting continents and seas spreading with my mother, she smirked at me and doubted ideas overboard.

I brought my teacher to my living place to talk and convince my mother, yet she had purposive doubt and seeming rejected it as an eccentric paradigm.

A few years later, i had convincing ideas and science, words of all great men on my side, to make her understand but by then she was no more.

LikeLike