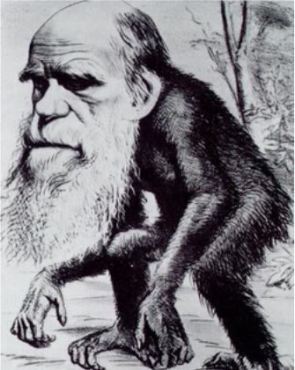

It’s his birthday. It seems Charles Darwin’s legacy is experiencing a renaissance. Sure, some 60% of Americans vilify the man and hope he is roasting in hell. Or undergoing reincarnation as a toad, or is still awaiting release from purgatory. I guess that the eternal damnable punishment for writing a pretty good book depends on one’s own vision of a just and loving supreme being. Darwin has somehow caught the heat and hate of a lot of people who have trouble with scientific inquiry – and where such inquiry may lead.

Nevertheless, few scientists were as meticulous, thoughtful, and cautious as Charles Darwin. Though we celebrate his ideas of natural selection, survival of the fittest, and the origin of species, the idea that biology continually sorts and rearranges itself evolved slowly in the years before Darwin. The notion of evolution became evident to other natural philosophers in the early 1800s. Before Darwin boarded the Beagle in 1831, he had already been exposed to the uniformitarian ideas of Lyell, Lamarckian evolution, and perhaps the works of Townsend, Wells, Matthew, and Adams – proponents of various schemes of natural selection, the effects of tooth and claw, and the malleability of species.

Although Origin of Species appeared 156 years ago, one could argue that the gospel of evolution is actually over 200 years old. Charles Darwin was the last of the first great apostles. He was expected to become a rural pastor, but like the man from Tarsus, he experienced unexpected insight and then wrote letters and books that became part of the greatest story ever told. But the analogy ends there. The theory of evolution is not a religion of inflexible dogma; it is an element of science – a restless collection of ever-changing observations and thoughtful interpretations. It is fraught with errors and flaws. What we believe to be true about science may be an illusion. Scientists accept this. They relish it, actually. The greatest joy and biggest impact any scientist may achieve comes in disproving something that everyone else holds dear. New observations sometimes markedly transform the truths revealed by earlier generations of scientists. We’ve seen this in plate tectonics, germ theory, subatomic physics, climate science, public health, and cosmology. We’ve seen corrections to theories again and again.

Amazingly, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution as presented in his book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (That’s the full title.) has changed little in 150 years. Subsequent discoveries have reinforced Darwin’s hypothesis. For example, Darwin wrote Origins almost 50 years before Mendel’s ideas of particulate inheritance were employed by de Vries and Correns. Mutations to alleles, caused by environmental damage from radiation and chemicals, was not imagined by anyone in Darwin’s day. Nor were genes and chromosomes, the helix of codes, DNA sequencing, recombination, RNA transfer, and instructions for protein production controlled by the order of just four chemical bases abbreviated as A, C, G, and T. Yet all of these new discoveries continually validate the basic theories that Darwin published in 1859. Any scientist who could prove Darwin’s take on evolution is fundamentally wrong will be hailed as the greatest scientist since Darwin. But so far, evidence just keeps piling up to support Darwin’s original idea.

Pretty good work for a Victorian-era geologist. Darwin was first noted as an accomplished rocks guy – biology came later. It might be more fair to describe him as a natural philosopher, as generalists were called in his day. He fell in love with geology on the third week of his 5-year voyage aboard the Beagle. Here is what he said about the Cape Verde islands when he first saw them:

The geology of St. Iago is very striking yet simple: a stream of lava formerly flowed over the bed of the sea, formed of triturated recent shells and corals, which it baked into a hard white rock. Since then the whole island has been upheaved. But the line of white rock revealed to me a new and important fact, namely that there had been afterwards subsidence round the craters, which had since been in action, and had poured forth lava. It then first dawned on me that I might write a book on the geology of the countries visited, and this made me thrill with delight.

– Darwin’s Autobiography, p. 81.

Darwin wrote that geology book, and several others. His major study on the Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842) upset existing coral theory. Darwin believed that since coral can’t grow in deep water, reefs must grow on slowly subsiding rocks. Coral continues to grow as the mountain supporting it sinks, leaving a fringing barrier reef and eventually an atoll. As a result, he said, the coral limestone could become miles thick, building on itself at the pace that the supporting mountain subsides. For over a century, there was debate about his theory. Darwin’s ideas was verified in 1951 when US geologists, checking out islands for atomic hydrogen bomb tests, drilled two holes in the Enewetak Atoll test site in the Pacific. They drilled through a kilometre of old coral and then reached a mountain of volcanic rock. The kilometre of old coral had originated in shallow water, demonstrating the subsidence of the volcanic mountain and continual growth of coral upon coral – proving Darwin was right.

Closer to his home in England, Darwin became a proponent of the unpopular idea that the Earth is very, very old. His study of the geology of the Weald Mountains resulted in his estimate that the range was at least 300 million years old. At the time, Lord Kelvin used the physics of thermodynamics to insist the Earth could not be more than 20 million years in age. Darwin was adamant – he had measured the rate of erosion of the Weald highlands and it would take 300 million years to reduce them to their present height. For this, and his many other geological studies, Darwin was awarded the Geological Society of London’s Wollaston Medal, Britain’s highest recognition for a geologist.

There is much more to say about Darwin and geology. For that, I have a lagniappe for you. Here is a Darwin’s Day gift, of sorts. What follows is pilfered directly from my book, The Mountain Mystery. It is a tale that recounts Charles Darwin’s gentlemanly skirmish with America’s greatest geologist of the time, James Dana. And it includes interesting correspondence written by Darwin which you have probably never seen before. And it traces the first stages of the reluctant acceptance of Darwin’s theory in America.

Here we go: James Dana was head of geology at Yale for 42 years. He married his Yale chemistry professor’s daughter, Henrietta Silliman. Dana was a respected gentleman who played piano at church, led Bible studies, and prayed over meals with his family. In his early 40s, he wrote Science and the Bible which attempted to reconcile geology with religion. But he kept his religious sentiments peripheral to his science. Unlike most of the earlier geologists, he didn’t try to distort his geological discoveries to match his spiritual beliefs. Dana worked in the opposite direction – he found biblical passages that confirmed what science was telling him. He fully accepted the Bible as God’s revelation, “But there are also revelations below the surface, open to those who will earnestly look for them.” (1)

There was one exception to Dana’s practice of finding biblical scriptures to justify scientific discoveries. He refused to reconcile evolution with his faith, even though he maintained a cordial correspondence with Charles Darwin. And Darwin with Dana. However, it seems neither one found it necessary to read the other’s books before criticizing them. You can see how this unfolded with the following exchange of letters in 1863. First, we find Dana writing to Darwin:

“The arrival of your photograph has given me great pleasure, and I thank you warmly for it. I value it all the more that it was made by your son. He must be a proficient in the photographic art, for I have never seen a finer black tint on such a picture.

“I hope that ere this you have the copy of Geology (and without any charge of expense, as this was my intention). I have still to report your book [The Origin of Species] unread; for my head has all it can now do in my college duties. I have thought that I ought to state to you the ground for my assertion that geology has not afforded facts that sustain the view that the system of life has evolved through a method of development from species to species. . .” (2)

In his letter, Dana then proceeds to list some basic errors in Darwin’s logic. Dana finds there are “missing links” between many species (though he readily adds that he knows that not all the world’s fossils have been discovered). Some species, according to Dana’s understanding of Darwin, developed from “higher groups of species instead of the lower,” implying a reverse evolution that would suggest Darwin’s basic theory was wrong. And some species seemed to go extinct in the rock record, but then somehow “started again as new species.” All of these criticisms from America’s greatest geologist were valid at the time. They were all subsequently resolved when the fossil record became more complete.

Darwin wrote back to his colleague:

“I received a few days ago your book and your kind letter. I am heartily sorry that your head is not yet strong, and whatever you do, do not again overwork yourself. Your book [Manual of Geology] is a monument of labour, though I have as yet only just turned over the pages.” (3)

It is interesting that two of the greatest geologists of the century couldn’t find time to read each other’s most important works. Darwin goes on:

“With respect to the change of species, I fully admit your objections are perfectly valid. I have noticed them. . . Nevertheless I grow yearly more convinced of the general (with much incidental error) truth of my views. . . As my book has been lately somewhat attended to, perhaps it would have been better if, when you condemned all such views [regarding evolution], you had stated that you had not been able yet to read it.” (4)

Darwin’s irritation with his friend at last surfaced. Dana had been publicly attacking Darwin for months without actually reading On the Origin of Species. It would take years, but incredibly, the book which sat unopened on Dana’s shelf was eventually read, appreciated, and accepted as fact by North America’s foremost geologist. In Dana’s 1896 edition of Manual of Geology, Dana completed his long treatise on geology with an unequivocal acceptance of Charles Darwin’s science – with one notable exception. In his final textbook, James Dana virtually gushed with admiration for the theory of natural selection and he admited that in the thirty years between his first rejection and his whole-hearted acceptance, science had found the missing fossils that had caused him concern. He listed the evidence: progress from aquatic to terrestrial life; progress from simple to more specialized; modern embryos, with “part of the early life of the globe” (5) represented in their development; “unity in the system of life” regarding how creatures are organically related (all are carbon-based life-forms); and, the increasing levels of cephalization, or brain complexity, as a function of time.

Dana summarized, “According to the principle of natural selection, an animal or plant that varies in a manner profitable to itself will have, thereby, a better chance of surviving, and of contributing its qualities and progressive tendency to the race, while others, not so favoured, or varying disadvantageously, disappear.” Dana conceded that the origin of the variations was unknown, but expected science to discover this, too. His book was published in 1896, the same year as the discovery of radiation, a key environmental cause now known to contribute to genetic variation. In his final book, Dana backed up his support for Darwin’s discoveries with dozens of specific examples. Years ahead of evolutionary biologists, Dana even correctly speculated that dinosaurs had evolved into birds. But James Dana never accepted that humans had evolved from earlier creatures.

Dana concluded his magnificent Manual of Geology with a lengthy discussion of Man’s pinnacle position in the biological order of life on Earth. “Man’s origin has thus far no sufficient explanation from science. His close relations in structure to the Man-Apes are unquestionable. They have the same number of bones with two exceptions, and the bones are the same kind and structure. The muscles are mostly the same. Both carry their young in their arms.” (6) And yet, James Dana, the piano-player at the church where he was a leader, cautioned against carrying the similarities too far, inviting the reader to crawl around on all fours like a great ape and see that humans don’t have the massive neck muscles required to keep the head level. He ended with “. . .the intervention of a Power above Nature was at the basis of Man’s development. Nature exists through the will and ever-lasting power of the Divine Being, and all its great truths, its beauties, its harmonies, are manifestations of His wisdom and power.” (7)

Over a lifetime of research, teaching, and writing, Dana had published two million words in his scientific books and papers. His influence was phenomenal not just in the role evolution plays – or does not play – in man’s ascent, but also in his approach to science. He was able to reverse his earlier instincts and accept most of the idea of evolution when the mass of evidence was finally clear. And, in his own mind at least, he was able to reconcile two dichotomous forms of revelation – stones from the Earth and messages from God.

In the end, James Dana was very nearly a Darwinian evolutionist. He stopped short of fully endorsing all aspects of evolution, namely man’s ascent from earlier forms, but his scientific mind could not reject the fundamental elements of life’s evolving nature. Charles Darwin’s patience and polite reception of his erstwhile adversary had everything to do with James Dana’s awakening and the subsequent arrival of evolutionary theory in America.

Notes:

(1) Dana, James Dwight (1856). Science and the Bible, p 81. Warren F. Draper, Andover.

(2) Dana, James Dwight (1863). Dana’s letter to Darwin, from New Haven, Connecticut, February 5, 1863.

(3) Darwin, Charles (1862). Darwin’s letter to Dana, from Bromley, Kent, February 20, 1863

(4) Ibid.

(5) Dana, James Dwight (1896). Manual of Geology, pp 1028-1035.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Ibid.

Reblogged this on the anthropo.scene.

LikeLike

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #35 | Whewell's Ghost

Reblogged this on The Mountain Mystery and commented:

I don’t often reblog, but it’s Darwin’s birthday. So I am repeating this piece from one year ago today. Have a slice of cake while you read it!

LikeLike

I’d say he fell in love with geology in July 1831 when he explored Shropshire and then went round N wales with Adam Sedgwick. I have several papers on it Here’s a summary https://michaelroberts4004.wordpress.com/2015/02/12/mad-about-geology-geologizing-with-darwin-2/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the link, I’ve been following your blog for a while. Thanks for contributing!

LikeLike

Pingback: Going on Four (Billion) | The Mountain Mystery

Pingback: The Making of Mountains: Cycles of Building and Decay (Part 4) – My planet blog