“Tuzo’s dead.” That was the first time I’d ever heard of Tuzo. It was April 1993 and I wondered who – or what – Tuzo was. Now he was dead. I had already completed my University of Saskatchewan geophysics degree but I couldn’t recall hearing about Canada’s greatest geophysicist. My ignorance was my own fault.

I had been focused on the theory of geophysics – signal processing, solid Earth dynamics, potential fields, anisotropic conditions, and the like. The professors at Saskatoon’s remarkable university imbued the ingredients that assured my success in science. There was a lot to absorb. At the end of each course, I squeezed my sponge-brain dry and moved on to the next semester. There was no time to indulge in a study of the context and environment of the subjects. Nor had it really occurred to me that some humans somewhere had invented all the geophysical things I had memorized.

To try to fill the gap – and fulfill graduation requirements – I took humanities electives. One was the History of Science, taught by an able young philosopher who introduced me to Kuhn and Cohen and Popper. I wrote a thesis on society’s acceptance of Einstein’s Special Relativity. Had I known about Tuzo Wilson, he would have been my subject.

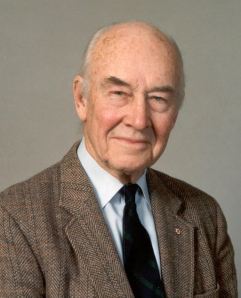

John Tuzo Wilson – called Tuzo by nearly everyone – indubitably revolutionized the way we understand the Earth. He had three great ideas that reinforced the nascent theory of plate tectonics. I will mention each briefly. But first I want to consider the versatile life of an established scientist who was able to change his mind about something important well into his middle age.

What follows is not a comprehensive biography of the great man, but rather a collection of some of his milestones. (In my book, The Mountain Mystery, I give Tuzo a broader treatment.) Tuzo’s mother carried the French Huguenot name Tuzo. From her, Tuzo inherited more than his middle name. Henrietta Tuzo was a fearless mountain climber. (In 1907, she and Christian Kaufman were first to climb Alberta’s Mount Tuzo, a peak so lovely it graced the Canadian 20 dollar bill for a long while.) Tuzo Wilson’s own love of mountains included his ascension of the Bear Tooth’s Mount Hague, conquered first by Tuzo while he was doing his PhD field research.

From his father, Tuzo Wilson absorbed engineering and science. His father, a Scottish immigrant, designed the Montreal and Toronto airports. With his father’s sense of project design and craftsmanship, Tuzo took to the air and photographed Canada’s Arctic. He developed the idea of remote sensing, figuring out how to collate aerial photographs with geologists’ field notes.

Tuzo had a precocious appetite for geology. At 15, he worked summers for the Geological Survey of Canada. He loved geology and he excelled in math and physics. It is not surprising that he earned the first geophysics degree awarded to a Canadian. After Trinity College in Toronto, he received a Massey Fellowship to St John’s at Cambridge, then finished his PhD at Princeton, in 1936. After Princeton, Wilson returned to the GSC and mapped much of Canada’s enormous Northwest Territories. With the start of war in 1939, Tuzo Wilson enlisted in the Canadian Army, finishing his service with the rank of colonel. After the war, he led Exercise Musk Ox, a 5,000-kilometre excursion through the Arctic – it remains the longest arctic vehicular trip ever undertaken. Upon discharge, Colonel Wilson became Professor Wilson at the University of Toronto. He stayed there for almost thirty years.

If it involved geology, Wilson had probably studied it. His interests were so wide-ranging that colleagues called him the cyclone scientist. He was internationally regarded for his work on glaciers, which led him to draft the first glacial map of Canada. As part of that study, he searched for ice patches on the arctic islands and became the second Canadian to fly over the North Pole. His experience in flight, mapping, and the Arctic merged into pioneering work in aerial photography. His photos were a key element in creating Canada’s geological maps. A view from above was an essential step in that tedious project.

Tuzo headed the department at U of T, ran the the Ontario Science Centre, and led Canada’s participation in the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958). After an IGY meeting in Moscow, at the height of the Cold War, Tuzo hopped a trans-Siberian rail and headed to Beijing. He was the first western scientist to visit Mao’s China. His book, Unglazed China, is one of the few glimpses the west had of Chinese science and culture immediately after the Communists consolidated their autocratic power. Tuzo Wilson returned in 1971, just before Nixon’s famous table-tennis expedition, and wrote a second book, highlighting the changes that transpired since the International Geophysical Year – changes which included the devastating Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Tuzo headed the department at U of T, ran the the Ontario Science Centre, and led Canada’s participation in the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958). After an IGY meeting in Moscow, at the height of the Cold War, Tuzo hopped a trans-Siberian rail and headed to Beijing. He was the first western scientist to visit Mao’s China. His book, Unglazed China, is one of the few glimpses the west had of Chinese science and culture immediately after the Communists consolidated their autocratic power. Tuzo Wilson returned in 1971, just before Nixon’s famous table-tennis expedition, and wrote a second book, highlighting the changes that transpired since the International Geophysical Year – changes which included the devastating Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

For years, if Wilson had any opinion about continental drift, it was a guarded one. Those who knew him said he didn’t find much value in the idea until about 1960. But after he contemplated the new evidence, Wilson decided the idea of moving continents fit the data and he became an unwavering advocate. His colleagues were much more reticent. As Tuzo Wilson himself said in this 1975 TV interview, “a lot of people weren’t happy about it, because they weren’t brought up with it – it’s like asking a middle-aged man to change his religion, and they don’t really like it. They would have been delighted to see something happen that would destroy it all, and go back to fixed continents!”

Tuzo Wilson was in his mid-50s, an age at which most scientists find change and innovation difficult. Tuzo, however, delighted in the challenge. It was then that he made his greatest contributions to science. He resolved three of the most vexing issues that threatened to derail plate tectonics theory: (1) As presented in 1962, the idea of continents in motion implied Hawaii and Yellowstone shouldn’t exist – they are remote from the energy sources of spreading ocean rifts and colliding continents. (2) Geologists made no sense of swarms of awkwardly positioned faults near rift zones – they weren’t within the style of typical faults. And (3) there was evidence that some mountain-building had inexplicably occurred at a time predating the supercontinent, Pangaea.

These three issues suggested flaws in drift theory. Wilson solved each without complicated mathematics. He used something he described as visual imagery – sharp pictures that formed in his creative mind. For example, in the case of Hawaii, he visualized the eerie scene of a girl lying on her back at the bottom of a stream. As bubbles surfaced from her mouth, they were swept away by the moving current. This is how he saw Hawaii – hot volcanic material rose to the crustal surface, building mountains that were ‘swept away’ by the moving seafloor. His ideas at first seemed outlandish, but geologists listened to Tuzo. He had a long-established reputation for getting things right.

He solved (1) Hawaii by introducing plumes – an idea that seemed so peculiar he couldn’t get it published at first. (2) The odd faults at rift zones were resolved when he invented transform faults. And (3), the apparent existence of mountains that predated Pangaea was explained by cycles of continental amalgamation and disintegration – others named these Wilson Cycles in his honour.

Tuzo Wilson, Canada’s Renaissance man, enjoyed educating and performing. In the 1970s, he created and hosted a 12-episode television series – The Planet of Man – in which he explained plate tectonics, fault systems, and mountain growth. These shows opened with Tuzo cruising lakes in northern Canada on his Chinese junk, a 12-metre craft that he said was well-suited for approaching isolated outcrops. Another venue for public education came late in life – he spent the eleven years up to his 76th birthday as director of the Ontario Science Centre. Because he had made such outstanding contributions to support plate tectonics, the Ontario Science Centre later built a three-metre-high memorial to commemorate Tuzo Wilson. The sculpture includes a spike jabbed into the ground. It indicates the distance the science centre has drifted away from Europe since Wilson’s birth. A remarkable monument that celebrates a man who spent most of his life skeptical of continental drift theory, but perhaps did more than anyone else to advance it.

Reblogged this on GeoKnow Blog and commented:

J Tuzo Wilson was a Canadian scientist whom every Canadian should know. I realize not all of us are Geo-Geeks, but the contributions this man made to our understanding of how the world works are immense. I remember first hearing of him in Mr Krummins’ Gr 11 Physical Geography course in 1978-79 and was fascinated. I imagine we watched Planet of Man, too.

In his blog post, Ron Miksha clearly explains the importance of “Tuzo”.

LikeLike

Thanks, Terry! Tuzo was an interesting scientist with extraordinary insights and skills. Thanks for keeping up his tradition at your own great geographic resource site – GeoKnow.net!

LikeLike

Pingback: Mantle Plumes May Be Real (or maybe not) | The Mountain Mystery

Pingback: Tectonic Plates at 913,000 Kilometres per Hour | The Mountain Mystery